Credit/ from Wikipedia

O.W. Gurley

Around the start of the 20th century O.W. Gurley, a wealthy black land-owner from Arkansas, came to what was then known as Indian Territory to participate in the Oklahoma Land run of 1889. The young entrepreneur had just resigned from a presidential appointment under president Grover Cleveland in order to strike out on his own."[9]

In 1906, Gurley moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma where he purchased 40 acres of land which was "only to be sold to colored".[9]

Among Gurley's first businesses was a rooming house which was located on a dusty trail near the railroad tracks. This road was given the name Greenwood Avenue, named for a city in Mississippi. The area became very popular among black migrants fleeing the oppression in Mississippi. They would find refuge in Gurley's building, as the racial persecution from the south was non-existent on Greenwood Avenue.

In addition to his rooming house, Gurley built three two-story buildings and five residences and bought an 80-acre (32 ha) farm in Rogers County. Gurley also founded what is today Vernon AME Church.[2]

This implementation of "colored" segregation set the Greenwood boundaries of separation that still exist: Pine Street to the North, Archer Street and the Frisco tracks to the South, Cincinnati Street on the West, and Lansing Street on the East.[2]

Another black American entrepreneur, J.B. Stradford, arrived in Tulsa in 1899. He believed that black people had a better chance of economic progress if they pooled their resources, worked together and supported each other's businesses. He bought large tracts of real estate in the northeastern part of Tulsa, which he had subdivided and sold exclusively to other blacks. Gurley and a number of other blacks soon followed suit. Stradford later built the Stradford Hotel on Greenwood, where blacks could enjoy the amenities of the downtown hotels who served only whites. It was said to be the largest black-owned hotel in the United States.[2]

Gurley's prominence and wealth were short lived. In a matter of moments, he lost everything. During the race riot, The Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood, the street’s first commercial enterprise, valued at $55,000, was lost, and with it Brunswick Billiard Parlor and Dock Eastmand & Hughes Cafe. Gurley also owned a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood. It housed Carter’s Barbershop, Hardy Rooms, a pool hall, and cigar store. All were reduced to ruins. By his account and court records, he lost nearly $200,000 in the 1921 race riot.[2]

Because of his leadership role in creating this self-sustaining exclusive black "enclave", it has been falsely rumored that Gurley was lynched by a white mob and buried in an unmarked grave. However, according to the memoirs of Greenwood pioneer, B.C. Franklin,[10] Gurley left Greenwood for California. Whichever version is true, the founder of the most successful black community of his time drifted into obscurity and almost vanished from history. He was honored in a 2009 documentary film called, Before They Die! The Road to Reparations for the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Survivors.[11]

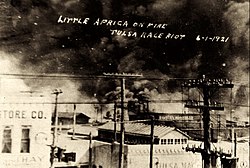

Tulsa Race Massacre

The Tulsa Race Massacre occurred in late May 31 and June 1, 1921. During the massacre, 35 square blocks of homes and businesses were torched by mobs of angry whites. The ransacking began because of the alleged assault of a white elevator operator, 17-year-old Sarah Page, by a black shoeshiner, 19-year-old Dick Rowland. The attack killed hundreds and left an estimated 10,000 people homeless. The city government of Tulsa conspired with the mob, arresting more than 6,000 black residents and refusing to provide them with protection or assistance.[12] Law enforcement officials used airplanes to drop firebombs on buildings, homes, and fleeing families, stating they were protecting against a "Negro uprising."[13] The massacre was omitted from state and local records, and "rarely mentioned in history books, classrooms, or even in private."[14]

The community mobilized its resources and rebuilt the Greenwood area within five years of the Tulsa Race Massacre in spite of political efforts to prevent reconstruction, and the neighborhood was a hotbed of jazz and blues in the 1920s.[15] During the Great Depression, however, the area became known for vice and crime.[16] The neighborhood fell prey to an economic and population drain in the 1960s, and much of the area was leveled during urban renewal in the early 1970s to make way for a highway loop around the downtown district. Several blocks around the intersection of Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street were saved from demolition and have been restored in recent years, forming part of the Greenwood Historical District.

Improvements

Revitalization and preservation efforts in the 1990s and 2000s resulted in tourism initiatives and memorials. John Hope Franklin Greenwood Reconciliation Park and the Greenwood Cultural Center honor the victims of the Tulsa Race Riot, although the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce plans a larger museum to be built with participation from the National Park Service.[17]

In 2008, Tulsa announced that it sought to move the city's minor league baseball team, the Tulsa Drillers, to a new stadium, now known as ONEOK Field to be constructed in the Greenwood District. The proposed development includes a hotel, baseball stadium, and an expanded mixed-use district.[18] Along with the new stadium, there will be extra development for the city blocks that surround the stadium. This project will bring Greenwood Historical District out front and center and attract not only tourists but also Tulsa residents to North Tulsa.